(This article was first published in China Diplomacy website in English and in Chinese language)

Our research into the Chinese “debt-trap” narrative, which the U.S. State Department has heavily promoted since May 2018 with substantial funding and media support, reveals no evidence to support such a claim. The narrative serves primarily as a geopolitical propaganda tool to impede the progress of the China-proposed Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and damage China’s international reputation.

Our analysis of financial and economic developments in countries such as Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Zambia, Kenya and Montenegro over the past decade reveals a consistent pattern. This pattern indicates that their financial distress stems from a combination of internal and external factors, none of which are directly attributable to China or the BRI. Through this investigation, we have developed a systematic method to highlight the main fallacies within this narrative. This investigative method can be applied to study any country allegedly victimized by “China’s debt trap” and thus separate facts from fiction. Furthermore, this investigation will help policymakers determine sound policies for infrastructure development credit in the next decade of the BRI, building the cornerstone of economic development for their nation.

The method suggests that anyone who accepts the debt-trap narrative must address three fundamental questions:

1. What is the composition of the country’s debt?

2. What is the quality of the debt?

3. What is the source of the country’s financial distress?

1. Debt composition

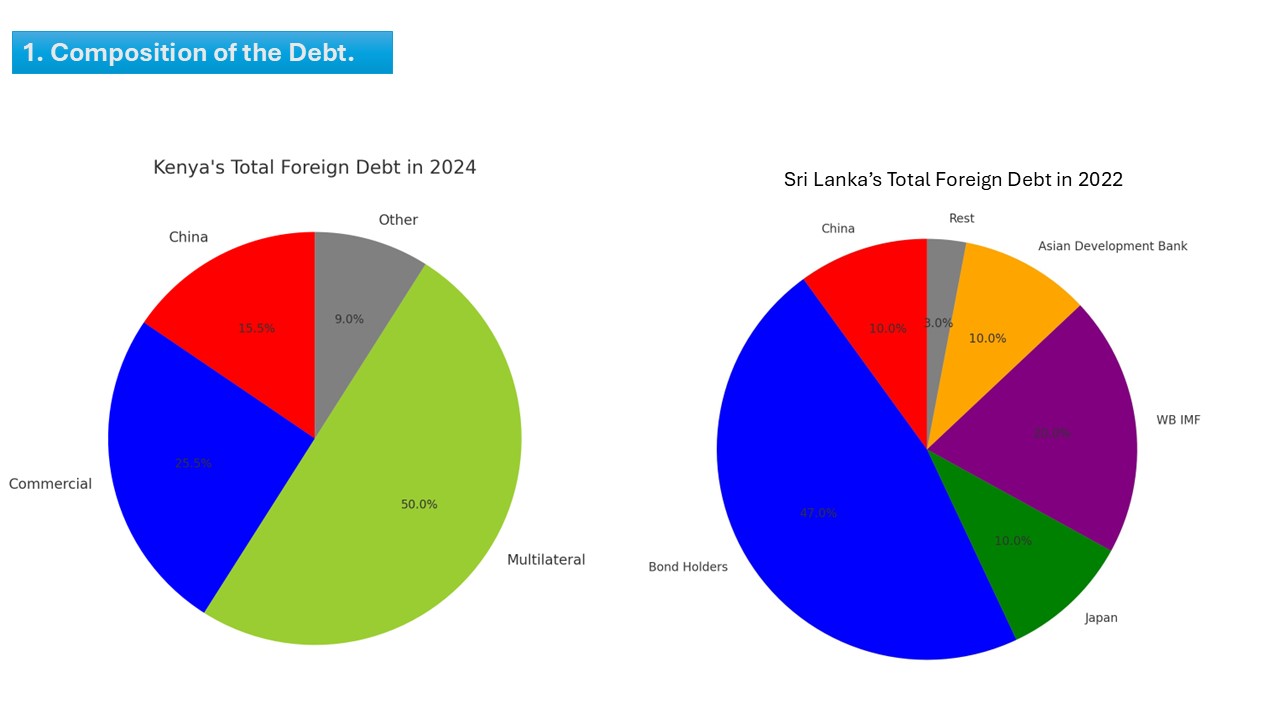

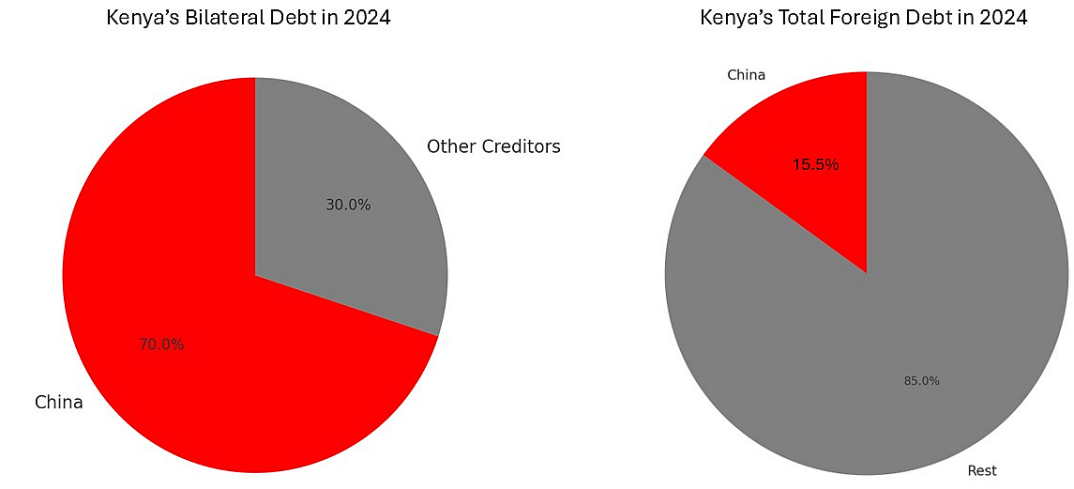

What is meant by “composition” is how much of a country’s total foreign debt is owed to various creditors, expressed as percentages [see Figure 1]. We immediately discovered that the portion owed to China represents only a fraction of the total debt (10% in Sri Lanka’s case in 2022 and 15.5% in Kenya’s case in 2024).

Figure 1. Total foreign debt of Kenya in 2024 and of Sri Lanka in 2022

[Data: Kenya National Treasury, Sri Lanka Finance Ministry; compiled by the Belt and Road Institute in Sweden]

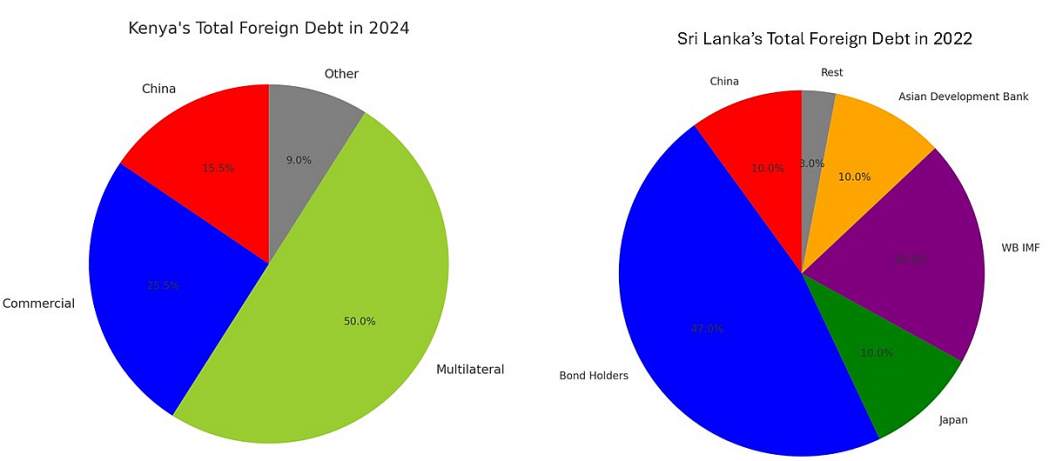

However, Western think tanks and media deliberately manipulate the semantics by focusing on the “bilateral” portion of debt rather than the total. They frequently highlight that “China is Country X’s largest bilateral creditor” [see Figure 2]. This selective framing creates a skewed perception of China’s disproportionate role in these countries’ financial problems.

Figure 2. Emphasizing Kenya’s bilateral debt with China rather than its total foreign debt

[Data: Kenya National Treasury; compiled by the Belt and Road Institute in Sweden]

Therefore, researchers should not rely solely on media or think tanks for information; instead, they should use publicly available official data from each country’s finance ministry or central bank. In Figure 2, we use information provided by the Kenyan National Treasury [January-2024-Monthly-Bulletin].

The composition charts of total debt reveal that China’s share of Sri Lanka’s debt is merely 10%, while 80% to 90% is owed to Western institutions or entities related to Western states. More importantly, the data exposes the “elephant in the room”: 47% of Sri Lanka’s debt comprises commercial loans owed mostly to private Western bondholders such as American BlackRock and British Ashmore. These bondholders own four times the amount of China’s loans to Sri Lanka. In Kenya’s case, the commercial loans exceed China’s share, and the multilateral loans, owed mostly to the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), are three times larger than China’s.

2. Debt quality

China’s loans under the BRI are almost exclusively directed toward building modern infrastructure in sectors like transport, power, water, education and health care. These projects are productive investments that increase recipient countries’ productivity. By enhancing infrastructure, the loans contribute to the industrial, agricultural and service sectors, enabling economies to generate income and create capacity to repay the loans. In contrast, most financial resources provided through commercial and multilateral loans are directed toward resolving fiscal and trade deficits. When countries face dire financial straits, like those mentioned above, they resort to heavy borrowing from international bond markets to solve immediate economic crises.

Countries borrow from bond markets to repay older bonds, often at much higher interest rates. In February this year, the Kenyan government faced a precarious situation as it lacked sufficient cash to buy back $2 billion in Eurobonds due in June. It managed to raise $1.5 billion through a new seven-year bond, but at an interest rate of 10% compared to the previous bond’s 6%. This piling up of new debt to pay back old debt at higher interest rates exemplifies a “poison pill.” Even if borrowed funds are used for infrastructure, borrowing short term for projects that are profitable only in the long term represents a classic mistake. This is one key cause of the real debt trap.

Another key qualitative difference is that Chinese loans offer longer repayment periods and lower interest rates. For example, the loan provided by the Export-Import Bank of China for Montenegro’s Bar-Boljare highway offers a 20-year repayment term, including a six-year grace period, at 2% interest. Similar rates and terms apply to the Mombasa-Nairobi and other railway projects in Kenya. On the other hand, commercial loans are shorter-term at five to seven years, with much higher interest rates of 6-12%.

China often provides debt rescheduling or relief for distressed countries, while Western bondholders resort to legal measures in Western courts to compel timely and full repayment.

Chinese loans have no political or economic strings attached, while Western multilateral loans often come with conditions such as currency devaluation, cuts to public infrastructure investment, enforcement of specific political changes and privatization of state-owned enterprises and natural resources. Cumulatively, these conditions lead to reduced economic productivity. The privatization of copper mining in Zambia under IMF directives, now controlled by Western multinational companies, has returned very little of its natural wealth to the Zambian nation. Therefore, this qualitative difference must be considered when investigating different cases.

3. The real causes of these countries’ financial distress

Many of these countries were already in financial distress before the BRI was launched in 2013. Afterwards, various internal and external developments augmented their difficulties. The causes range from civil wars, terrorism, epidemics, pandemics, financial mismanagement to corruption and changes in the global financial and monetary system. None of these are related to China. We can list some key causes:

a. Many countries rely heavily on one or two primary income sources, making them vulnerable to price shocks or activity fluctuations. For example, both Sri Lanka and Montenegro depend heavily on tourism. When Sri Lanka was hit by terrorism in 2017, tourism declined dramatically. As soon as it recovered in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic struck. The pandemic also severely affected Montenegro’s economy in 2021 and 2022.

b. Sri Lanka’s economy faces low productivity challenges. Its textile industry relies on imported machinery, fuel and cotton, adding value only through low-cost labor. When fuel prices rose globally in 2022 after the Ukraine crisis began, profit margins eroded completely.

c. Many nations in this category depend on imported oil, gas, and fertilizers for agriculture. Some borrow from foreign sources to import food. When global prices increase, these nations are hit hard.

d. Currency devaluation significantly increases debt burdens. Because foreign loans, including Chinese ones, are denominated in U.S. dollars, currency devaluation forces nations to pay more in national wealth to repay the same dollar amount of dollar debt. When the Biden administration passed the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022, the U.S. dollar rose against almost all global currencies, dealing a severe blow to indebted countries.

Conclusion

Examining and addressing these three key questions can provide a more accurate and objective evaluation of these nations’ debt crises. China is not responsible for causing these problems. In fact, China’s approach of issuing productive credit to these nations will help them escape the debt trap in which they have been ensnared for a long time. By providing favorable financing for infrastructure, these nations will be better positioned to increase productivity, rebalance finances and repay their dues to both China and other creditors. In this sense, China and the BRI are part of the solution to debt problems rather than their cause. However, China alone cannot resolve all the problems faced by these nations. There is a need to devise new methods of financing infrastructure and development. This will be addressed in a separate article.

This article is based on Hussein Askary’s presentation at the conference session “The BRI and the Global South,” chaired by Professor Li Xing at the 2024 International Think Tank Forum of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road.

Hussein Askary is vice chairman of the Belt and Road Institute in Sweden.

Li Xing is a Yunshan Leading Scholar and professor at the Guangdong Institute for International Strategies in China. He also serves as an adjunct professor at Aalborg University in Denmark.

Watch video of Askary’s lecture explaining this method in detail!