Hussein Askary

Vice-Chairman of the Belt and Road Institute in Sweden

The Lowy Institute’s recent report “Peak repayment: China’s global lending” by Riley Duke on China “becoming a net debt collector rather than a creditor” contains grave fallacies and omissions that reveal a great deal of incompetence and a certain measure of malice. “Fallacy of composition” is defined as an act where the writer assumes that something is true of the whole from the fact that it is true for some part of the whole. The latter could be either a silly mistake, which is not worthy of those who consider themselves as experts, or an intentional act of deception. “Lying by omission”, which involves leaving out important details to create a false impression, is essentially telling only part of the story to make someone believe something that isn’t entirely true. This form of deception can be just as harmful as outright lies.

The Lowy report’s fallacious assumptions about the role of China’s lending to developing nations in the context of the Belt and Road Initiative have been copy-pasted in many western mainstream media (for example, the Guardian, Reuters, and Newsweek). Some media in countries with bias against China such as India and Qatar also publicized it. Even in some misguided Asian and Chinese (Hong Kong) media like the South China Morning Post the disinformation was conveyed “objectively” with no critical examination. Naturally, some Western think tanks who don’t do much thinking for themselves, immediately jumped on board to propagate this disinformation. No verification or fact checking is done regarding the data and sources the Lowy Institute author claims to base his claims on in any of these media reports that look like a coordinated assault on China and the BRI.

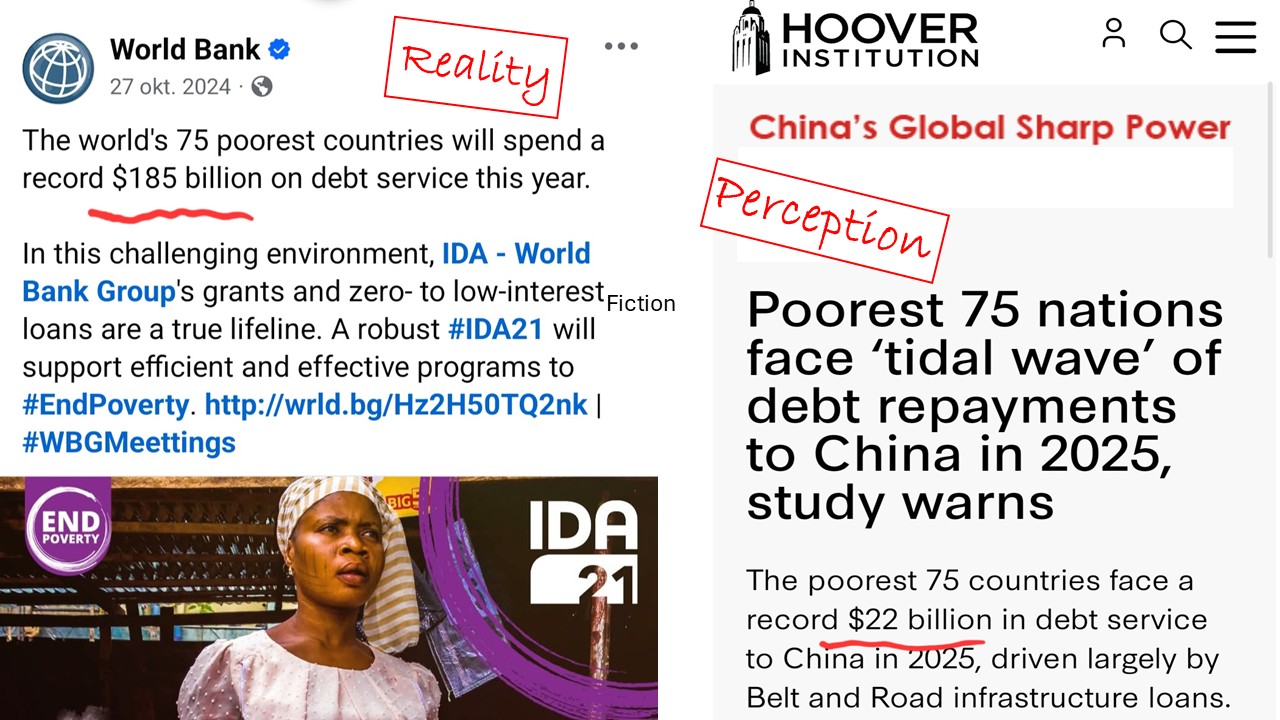

A simple fact checking of some of the sources reveals glowing discrepancies between reality and the perception created concerning facts Duke claims to have unearthed. Let’s take this one which became a headlines grabber: “Debt service flows to China from developing countries will total $35 billion in 2025 and are set to remain elevated for the rest of this decade. The bulk of this debt service, some $22 billion, is owed by 75 of the world’s poorest and most vulnerable countries”, he wrote. By omitting what these countries owe the rest of the world outside China (mostly Western institutions) and magnifying China’s share we can conclude that there is no mistake here but outright falsification. According the to the World Bank data and reports by the UN Development Program (UNDP), developing nations’ total debt service in 2023 reached US$ 1.4 trillion. So, China’s share of that is only 2,5% (!!!). As for the much-touted debt service of the 75 poorest countries, it reached US$ 185 billion. China’s share (US$ 22 billion) is thus just 12% of the total. Duke describes this small percentage, and is quoted verbatim in all Western media, as a “tidal wave of debt repayments”.

So, how did this small Chinese share become, magically, the largest obstacle to development and the greatest source of suffering of poor, poor developing nations?

Here comes the “fallacy of composition”.

Anatomy of the fallacy

The central fallacy upon which Duke’s case against China is based on is the premise that China is “the largest bilateral creditor” in the world. The term “bilateral” is used 16 times in the report. As I show below, bilateral loans, which are government-to-government credit agreements, are just a small “part” of the “whole” of the foreign debt stock of nations in the developing sector. The greater part of the debt burden, which the Lowy Institute intentionally “leaves out”, is the debt to Western (mostly American and British) “commercial creditors” like sovereign bond holders, and to “multilateral creditors” where Western-dominated institutions are the key players such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Asian Development Bank (ADB), and Paris Club. If we put the three categories (bilateral, multilateral, and commercial) next to each other for any country being described as “victim of Chinese debt trap” we immediately discover that Chinese loans are a small “part” of the “whole”, and that the real debt trap is caused and pursued by Western players.

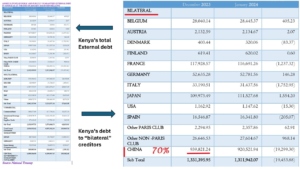

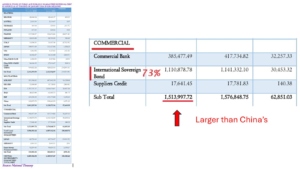

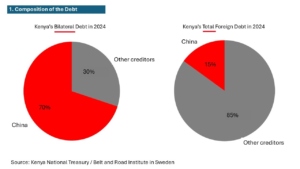

Kenya’s debt composition: In this series of charts derived from a January 2024 bulletin by the Kenya National Treasury [January-2024-Monthly-Bulletin], we can dissect the fallacy of composition. The numbers given here are in Kenyan shillings, but what is important is the percentage. If we just look at the sections marked as “bilateral”, China’s share of Kenya’s debt looks immense.

If we compare it to the section labelled “multilateral”, the picture starts to look different.

And when we look even further to the section labelled “commercial”, the picture changes again.

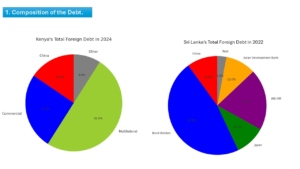

Finally, when we look at the “whole” and compare it to the part “bilateral”, the real picture emerges. China’s share of the total debt of Kenya is a small portion. This can be applied to any country and the result will look relatively similar as I did with the case of Sri Lanka, Zambia, and Pakistan.

Figuring out the “composition of the debt” is a very simple and accurate way of showing who is the largest holder of the debt of any country. Information about this is available from international institutions and national governments.

The composition of the debt of all developing countries. See original version on the website of the UNDP https://data.undp.org/insights/debt-in-developing-economies.

Furthermore, when we examine the “quality of the debt” which includes the maturity periods, interest rates, and most importantly, for what purpose its deployed, we discover that Western credits and loans are of a destructive nature and self-feeding debt accumulation, while the Chinese debt is meant to increase the productivity of those nations (through modern infrastructure) and thus the ability to repay their debt. One more factor that is totally ignored by Western think tanks and media is “where does the financial distress of that nation comes from”.

These three points (1. composition of the debt, 2. quality of the debt, and 3. causes of financial stress) constitute the key factors in my developed method of finding out in any given case whether China is guilty of “debt trapping” that country or not. (Read a short description of this method here, and a class explaining it in detail here).

By only focussing on “bilateral debt” and only on China, while ignoring all the other factors, Duke is misleading his readers. If he pleads incompetence, that might help remove the suspicions of malice. It does not help him though that his focus is turned towards the “repayment process” of Chinese loans which is allegedly peaking now, a none issue which we can deal with in a separate article, since the key premise of his thesis is based on the selective choice of “bilateral loans” extended by China to developing nations. The reason China’s loans to developing countries slowed down somehow in recent years are many, such as the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic which stalled many projects and nations were thrown into deep financial crises. Another important reason is that nations have been pressured by Western institutions like the IMF and World Bank to cease taking loans from China for investments in infrastructure and follow an austerity policy to deal with their financial problems that stem from COVID-19, and other causes not related to China and the Belt and Road Initiative. As I documented in my case studies of Zambia, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan, these pressures were expressed in public.

Nations are also advised by Western institutions and powers to not to take loans but instead ask for direct investments by China or enter into Public Private Partnership agreements with Chinese companies, so their balance books don’t look negative. But China has not ceased its support for infrastructure projects in Belt and Road countries such as the $8.3 billion railway project in Vietnam and the high-speed railway connecting Laos to Thailand. In the Summit of the Forum for China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in 2024, President Xi Jinping pledged RMB 360 billion (ca US$ 50 billion) in new financial support to African nations in the next three years, of which two thirds are in loans and one third in investments. At the same time, China continued to offer debt relief and rescheduling for a great number of nations, especially the poorest countries.

The simple reason that China ranks as the “largest bilateral creditor in the world” is that China’s government banks such as Export Import Bank and China Development Bank are the main creditors to Belt and Road Initiative infrastructure projects in the Global South. The loans are extended through government-to-government agreements. There are no “private” Chinese banks or bondholders involved in external lending. On the other side, no G-7 or Western state has its own state-owned bank to lend to developing countries, except through export credit guarantees to loans extended by Western private banks to developing countries. The 2015 Siemens mega deal to build gas-driven power plants in Egypt is a good example of such a sound state-backed export credit policy. But, the loans are still extended by private German banks. It is for this reason that Western countries in the chart of Kenya have a miniscule portion of the country’s debt compared to China’s.

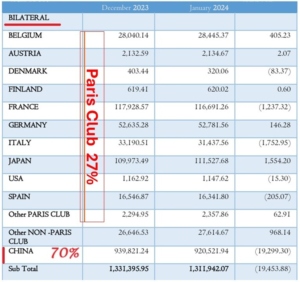

Second fallacy, Paric Club v China

Duke writes: “In 54 of 120 developing countries with available data, debt-service payments to China now exceed the combined repayments owed to the Paris Club – a bloc that includes all major Western bilateral lenders.” He provides glossy graphics comparing China to the Paris Club. However, a simple fact checking, as we do below, the Paris Club is no longer a major creditor to developing nations. As western economic powers ignored the importance of lending to infrastructure as part of alleviating poverty and bringing development, they have been replaced, especially since the 2008 global financial crisis, by Western private investors, such as Blackrock and Ashmore, and banks who buy the sovereign bonds of nations in desperate situations at high interest rates and short maturity terms. Therefore, it is ridiculous to compare China to the Paris Club. In the case of Kenya (See chart below), the Paris Club holds less than 6% of the country’s external debt. Therefore, comparing China to the Paris Club rather than the “multilaterals” who hold 50% or the “commercial” with 25% is another fallacy and flagrant omission.

China versus Paris Club. The latter is no longer a major creditor and has been replaced by private bondholder. In Kenya’s case, the Paris Club holds less than 6% of the external debt.

Further untrue statements:

– “For the poorest and most vulnerable countries, payments to China make up a quarter of all debt service costs, outweighing both multilateral lenders and private creditors. No single bilateral creditor has been responsible for such a large share of developing country debt service in the past 50 years.” This is totally fake. The author gives no data or evidence backing his claim that Chinese debt service “outweighs both multilateral and private creditors”. But then again, he returns to the “bilateral” creditor story. There are hardly any other “bilateral” lenders than China on the charts of nations as explained above.

– “Rising debt-service costs raise questions about whether China could use the repayments for geopolitical leverage. Some argue that China’s lending boom in the 2010s reflected an intentional effort at ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ aimed at pushing countries into debt problems so that geopolitical concessions could later be extracted. There is limited evidence to suggest that this was the purpose of the Belt and Road Initiative lending surge.”

Duke suggests first that there is a potential that China will use the debt stress of nations for geopolitical goals citing a geopolitically deranged and biased view with no factual substance. Then, he twists and turns language upside down suggesting that Dr. Deborah Brautigam showed that there is “limited evidence” of debt trapping. The truth is that the incredibly meticulous and admirable work of Dr. Brautigam shows that there is “no” evidence of a Chinese debt trap and that the whole narrative is based on “a myth”. She has been the leading systematic debunker of this myth. Using her work as a footnote to support a false claim is indeed disrespectful.

Conclusion

The purpose of my insisting on debunking claims of China’s alleged “deb trap” is not a defence of China, a nation powerful enough to defend itself. My aim is to defend the Belt and Road Initiative as an idea and as the most important and effective development plan in the history of mankind. The infrastructure projects built by China in the frame of the Belt and Road have contributed greatly to development goals of many nations. But they are still too few in my opinion to overcome the poverty and economic backwardness of many nations in the Global South. Even in developed regions there is much need for infrastructure building. I have discussed the enormous gap in funding for infrastructure in Asia and Africa in other articles. I argue, like economist Jeffrey Sachs has done in recent years, that not only China should continue and increase its productive credits to infrastructure projects in developing nations, but that these nations must borrow much more for this purpose on condition that the interests rates are low and the maturities are of 25 year or longer. Nations and regions should also establish their own “national development banks” and regional banks similar to the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the BRICS New Development Bank.

In addition, a general debt-moratorium and debt jubilee must be declared to rid nations of the chains preventing them from achieving their development goals.

China has done the right thing by launching the Belt and Road Initiative and financing it. More than 150 nations have joined it paying no attention to all the smear campaigns levelled against it by Western media, think tanks, and politicians. It is time the West joins hands with China to contribute to this process for the benefit of the world and their own. My native country Iraq needs it and my naturalized country Sweden does too.

Related Items:

Check The Facts of Sri Lanka’s Debt Crisis: No Chinese Debt-Trap! – Belt & Road Institute in Sweden

Debt Trap 2.0 and The End of Fukuyama – Belt & Road Institute in Sweden

Podcast #9: The Final Demise of the Chinese Debt-Trap Narrative – Belt & Road Institute in Sweden