Hussein Askary

With Chancay Port’s inauguration on Thursday, November 14 by Peruvian President Dina Boluarte and President Xi Jinping, the deepwater port developed by China’s Cosco Shipping is set to revolutionize regional connectivity, trade, and economic development in large parts of South America by accommodating the world’s largest cargo ships and significantly reducing shipping times. With a maximum depth of 17.8 meters, the Chancay Port can accommodate ultra-large container vessels. This largest Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) project so far in the American continent, is designed to handle an annual throughput of one million TEUs, 6 million tonnes of general cargo, and 160,000 vehicles. Transit time to Shanghai will be slashed from 35 days to 25 days, cutting costs for exporters who currently rely on routes through the Panama Canal or the Atlantic Ocean. The Port is projected to generate $4.5 billion in annual economic benefits for Peru, equivalent to 1.8% of its GDP.

In general the basis of the BRI collaboration is not merely building this very important port, but also the related bi-oceanic high-speed rail corridor linking Peru’s Pacific coast with Brazil’s Atlantic ports, which is the basis for creating “development corridors”, which even U.S. companies could be participating in, side by side with China, exporting high-tech capital goods and other products and helping to advance the living standard and skill level of the local population.

Transcontinental Development

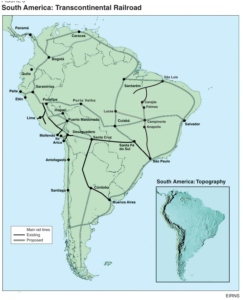

In a book-length report published in 2014 by Executive Intelligence Review, for which this writer was a co-author, an outline for the development of the continent was described in detail. This port and the related transcontinental railway, in addition to a flurry of other mega projects, would be the basis for an economic revolution. The report stated that inn South America, The attached map shows key priority rail routes to be built, both to ring the continent, proceeding along the Andean spine in the West, as well as across the mountains, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific. This kind of network will act to integrate growing economic activity. As of mid-20th Century, parts of Argentina and Brazil had relatively dense regional rail networks, which were undermined over the past 40 years. A continental grid was never built at all. The little that currently exists is indicated on the map, often reflecting the classic colonialist policy of building a railroad leading only from a mine to the port, so that raw materials could be exported for foreign exchange, which was then used to pay the ever-growing foreign debt.

This overall rail project took a significant step forward at the 2014 BRICS summit, where the idea of fulfilling the centuries-old dream of building a transcontinental railroad to connect the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of South America was taken up among Brazil, Peru, and China, in discussions between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Peruvian President Ollanta Humala, and then with Brazil’s President Dilma Rousseff (currently the Director of the BRICS New Development Bank). An agreement was reached to open bidding for foreign, including Chinese, companies, to participate in the construction of one critical segment of that project: the “T”-shaped Palmas-Campinorte Anapolis/Campinorte-Lucas route in central Brazil.

The importance of that segment within the overall project presented in the map is clear. The northern terminus of Palmas is a stone’s throw from the famous Carajás project in the middle of the Amazon jungle, the world’s largest (and purest) iron ore deposit, which is now connected by rail only to the Atlantic port of São Luis. Once built, the western rail terminus of Lucas would then be halfway to the Brazil-Peru border, where the projected rail line would link up, in one option with a Peruvian branch that would cross the Andes at Saramirisa—the lowest pass in that giant mountain range—and from there, to one or more Peruvian ports for shipment across the Pacific Ocean. This would drastically cut shipping time and costs from Brazil (and other Southern Cone countries including Argentina) to Eurasian powerhouses such as China, India, and Russia.

Even greater efficiencies, growth, and productivity can be achieved as this South American Transcontinental Railroad is able to connect directly by rail with Asia, as super high-speed rail lines are constructed through the Darien Gap and the Bering Strait. There are various possible routes for a South American Transcontinental Railroad. The one which was under discussion among China, Brazil, and Peru centred on São Paulo-Santa Fé do Sul-Cuiabá-Porto Velho-Pucallpa-Saramirisa Bogotá-Panamá, with Andean crossings at either Pucallpa or Saramirisa. Another viable option, which has long been studied, is São Paulo-Santa Fé do Sul-Santa Cruz-Desagua dero-Saramirisa-Bogotá-Panamá, with Andean crossings at Desaguadero, Pucallpa, or Saramirisa.

As President Xi will visit Brazil after Peru, many of these projects might come to light again, many years after they were envisioned, like the Chancay Port, which is now a reality.

Friendship and cultural relations

As the Belt and Road Institute in Sweden has explained repeatedly, the BRI is not merely about practical business deals, but a whole method of building a model for eradicating poverty and ushering prosperity, scientific and technological progress, peace and security, and above all a dialog of cultures. President Xi does not miss a chance, when visiting other nations to point out at this harmonic relationship between economic and cultural cooperation. Before arriving to Lima, tha capital of Peru, President Xi wrote an op-ed titled “China-Peru Friendship: Setting Sail Toward an Even Brighter Future”

and published in the official daily of Peru, El Peruano. Xi reminds that Peru and China’s close relations stretch from the extensive Chinese immigration to Peru which began 175 years ago, to Peru having been the first nation in Ibero-America to join the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which it did in 2019. Today, he reports that he and Peruvian President Dina Boluarte will attend the inauguration ceremony of Chancay Port, by video from Lima. This port is not only an important BRI project, but the first “smart port” in South America, he points out. It will cut the costs of shipping between Peru and China by at least 20%, generate an expected US$4.5 billion in annual revenues, create over 8,000 direct jobs, and “enable Peru to put in place a multi-dimensional, diverse and efficient network of connectivity spanning from coast to inland, from Peru to Latin America, and further on to the Caribbean … an Inca Road System of the New Era with Chancay Port as its starting point, thus boosting the overall development and integration of the region.”

Xi emphasizes the link between the ancient civilizations of China and Peru. “It is widely believed in the archaeology communities of China and other countries that the Chinese civilization and the civilizations of the Americas were in fact created by descendants of the same ancestors at different periods and different locations,” he writes. He points out that many Chinese and Peruvians have a feeling of “déjà vu when appreciating each other’s ancient artifacts. For example, the gold masks of the Incas unearthed in Peru are strikingly similar to the gold masks uncovered at an archaeological site at Sanxingdui in China’s Sichuan Province. The Intihuatana stone on an altar in the ancient city of Machu Picchu, which the Incas used to mark the seasons and compose calendars according to changes of solar shadows, was in fact based on the same principle that inspired the creation of sundials in ancient China.”

Xi proposes the two countries “stand up to the responsibility to our times concerning mutual learning among civilizations. We should strengthen exchange and cooperation in culture, arts, education, scientific research, tourism, youth, cultural heritage protection, archaeology and other areas…. We should enhance cooperation under the framework of the Ancient Civilization Forum. We should explore the establishment of a global network for dialogue and cooperation among civilizations…. We should ensure that civilizations, diverse in many ways, complement each other and shine brightly together, just like the multi-colored pools of China’s Jiuzhaigou and Peru’s Salt Terraces of Maras, thus making greater contributions to the progress of human civilization….

“China is ready to join Peru in embracing a broader vision and grasping the underlying trends of our times from a long historical perspective to champion true multilateralism, promote an equal and orderly multipolar world and a universally beneficial and inclusive economic globalization, jointly implement the Global Development Initiative, the Global Security Initiative and the Global Civilization Initiative, and build together a community with a shared future for mankind.

“As our friends in Latin America often say, without courage, one will never conquer the mountains or cross the sea….”

Sour grapes in Washington

But official Washington is proclaiming that the Chancay port is a plot by the Chinese to take over the region and steal resources that rightfully belong to the United States, and that the U.S. should take measures to stop such bold steps towards regional economic development.

U.S. Army War College Latin American studies professor Evan Ellis in his attack (https://ssi.armywarcollege.edu/SSI-Media/Recent-Publications/Article/3959936/strategic-implication-of-the-chinese-operated-port-of-chancay/ ) on the Chancay Port, published two days after the U.S. election, Ellis portrays the Peruvian government as weak, vulnerable and probably corrupt for allowing COSCO to build and operate such a critical port complex—which, by the way, no U.S. company had offered or intended to build. He twice suggests that officials approving the contracts likely received “direct or indirect personal benefits,” an obvious call for “anti-corruption” investigations to be used to take the port’s operations out of the hands of COSCO.

But what really concerns Ellis is the prospect that when President Xi Jinping visits Brazil next week, Brazil might also join China’s Belt and Road Initiative, as Peru has, or at least sign agreements with China for “a new railway connection, as well as improved Atlantic to Pacific roads to better connect the agricultural and mining belt in the interior of Brazil to the Port of Chancay on the Pacific.” He specifically denounces any transcontinental railroad which could potentially give Chancay “even more utility, connecting the Pacific to commodities and markets in Brazil and elsewhere in the continent.”

Ellis’s attack on Chancay pivots on the dominant view of the Pentagon, and the U.S. Southern Command: A war between the United States and China is inevitable. “In a time of war between the P.R.C. and the United States, the port of Chancay could potentially be used by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy to resupply forces and otherwise support operations against the U.S. in the eastern Pacific,” he writes. Peru is sovereign, but it must handle the port “in ways consistent with … its international responsibilities to allies such as the United States.”

He threatens: “Beyond Peru, other states in the region should learn from the lessons of Chancay.”

While in certain circles in Washington everything sweet may turn into something sour quickly these days due to a geopolitically-minded, zero-sum-game obsessed mindset, the rest of the world, especially in the Global South, is moving fast forward towards establishing a system of governance based on win-win cooperation and making an ever larger pie of economic prosperity rather than fighting over a shrinking pie in the imagination of formerly powerful group of nations. It is hoped that the election results in the U.S. and recently in Europe will stimulate the leadership there to take into consideration the interests and aspirations of their peoples rather than some imagined sense of supremacy and grandeur.