Hussein Askary

Vice-President of the Belt and Road Institute in Sweden

Distinguished Research Fellow of Guangdong Institute of International Strategies

May 5, 2024

This article was written for Geostrategic Pulse, a publication in Romania. It predates the visit by President Xi Jinping to Europe and President Vladimir Putin to China.

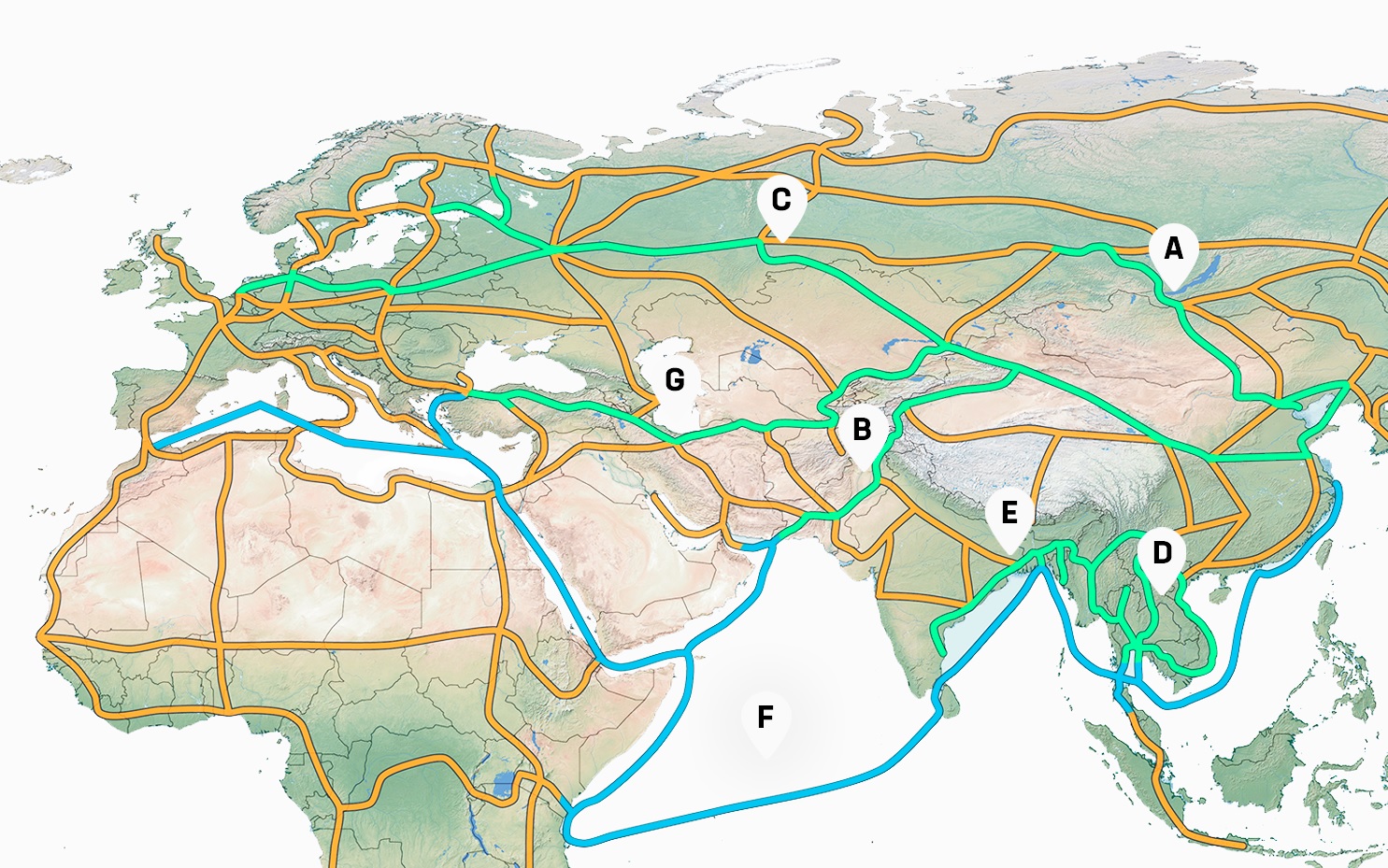

While the world has been rocked by a series of financial, economic, strategic and security crises in the past ten years, other processes of a constructive nature have been progressing unhindered. The rise of China as the world’s largest industrial economy, and with it the rise of many Asian nations, has continued and accelerated despite major impediments like the trade war with the U.S., COVID 19 pandemic, and the global inflation crisis following the launching of the war in Ukraine by Russia in February 2022. Another such process was the expansion of the Belt and Road Initiative to include 152 nations in 2023 by the time of the celebration of the tenth anniversary of its launching in 2013. The Expansion of both the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation westward to include Iran as a full member, and Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Qatar as observes, and more importantly, the expansion of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) to include Iran, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, and Ethiopia as full members, all have contributed to the creation of a new Eurasian reality which is more determined by geo-economics rather than geopolitics. The withdrawal of the U.S. and NATO troops from Afghanistan in August 2021, symbolically marked the end of more than 200 years of the geopolitical Great Game. The fact that China rushed to establish formal relations with the Taliban-controlled government in Kabul was more than a symbolic gesture.

China as the industrial superpower

A number of indicators published in the 2023 OECD Trade in Value Added (TiVA) and analysed by Professor Richard Baldwin should send shivers down the spines of geopolitically-minded Western leaders who wish to see China’s economy slowing down or grinding to a halt.

First, China continues to be the world’s largest manufacturing economy, holding 35% of the world manufacturing. All G-7 countries combined cannot reach this level, with the U.S. keeping 12%. China is also the absolute leader in creation of added value in manufacturing, holding 29% of the world’s total, with the U.S. lagging behind with 16% and the rest of the G-7 with 17%. Another extremely important indicator is the exposure to foreign supply chains, and how dependent the Western industrial nations are on China even in their own industrial production as their imports of intermediate goods from China has increased dramatically since 2002. China by now has built an astounding industrial supply chain at home. It has also achieved an absolute monopoly of certain sensitive sectors like the refining and supply of rare-earth metals with a 95% control of the global supply. This means that the U.S., for example, became by 2022 three times more reliant on China than China is on the U.S. as the source of industrial inputs.

On telling example of this process was revealed in December 2023 in South Korean media which reported that “Korea has suffered a trade deficit with its biggest market China this year for the first time in 31 years”. According to the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, Korea’s exports to China totalled $114 billion in the first 11 months of 2023, while imports amounted to $132 billion, resulting in an $18 billion deficit. One of the explanations given for the deficit against the Chinese market is that China no longer needs to import a large number of industrial and technological components from South Korea, because these can be produced now domestically in China. What this factor means is that decoupling by the West and other industrial powers from China has become impossible.

By 2030, China is intending to become the dominant manufacturer in such areas as aerospace equipment, aircraft, high-end CNC machines and basic manufacturing equipment, robots, engineering machinery and biomedicine industries. China is already the world leader in construction sectors like high-speed and standard-gauge rail and associated infrastructure such as tunnelling and bridge building. China is also the world leader in hydropower construction. It is making major advances in commercialization of its domestically-developed third generation nuclear power plants (with two plants in Karachi, Pakistan) and also the new fourth generation High Temperature Gas-Cooled Reactor-Pebble-bed Module (HTR-PM) . .

New markets and partners

Another indicator of significance that these statistics reveal is that China’s reliance on the American market for selling its products is decreasing. It is a matter of fact that some of the new emerging major trade partners of China are its own neighbours in the ASEAN (Association of South-East Asian Nations), the RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership) which includes ASEAN plus Japan, South Korea, New Zealand and Australia. The Arab countries are another emerging trade and economic partner that has the potential to surpass the EU in its importance for China in the coming years. The fact that China has replaced the EU as Russia’s main trade partner and helped it survive the sanctions and isolation imposed on it should ring alarm bells in the power corridors of the West.

What these factors imply for the nations of the Global South and to be a partner of the world’s largest manufacturing power is that the tools of economic progress, i.e. machinery and technologies of all kinds are now available from China. China has shown willingness to share these tools with other nations, for example through the Belt and Road Initiative, but always staying ahead of the wave technologically. Here, the issue is not the much-hyped Chinese export of solar panels and electric vehicles, which are of interest mostly in Europe and the U.S. and not in developing countries. Developing countries in Asia and Africa need construction machinery, infrastructure engineering, telecommunications, power generation capacity, healthcare and skill capacity development. Nations in Africa and Latin America are realizing that they have been robbed through the process of being mere suppliers of cheap raw materials to an industrial world which would resell finished products to them with a much higher added value. Nations in Africa are demanding that they become part of the industrial supply chain. For example, Zimbabwe banned the export of raw lithium in 2023 and declared that it would only cooperate with nations that help build a domestic lithium battery industry in Zimbabwe. China was readily willing to comply, because it would be a winner no matter how the coin falls, as it has the technology and capacity to provide the industrial equipment for those countries to industrialize. China is assisting Ethiopia in its plans to build industrial parks where textiles, leatherware, and even car assembly lines for production of affordable Chinese cars for the national and Africa markets are being built.

New Go West Strategy

China is developing a new strategy of “going west” pivoting on making Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region a launching pad and centre for this policy. I explain this policy in a detailed report I wrote recently after touring the region. The policy focuses on making Xinjiang both as an industrial and logistics hub focussing on trade with Central Asia, West Asia, and Europe. The Chinese government is pouring unfathomable amounts of money in investments in new infrastructure and industrial and logistics zones in Xinjiang, reaching the equivalent of US$ 70 billion only in 2023.

In May 2023, a historic summit held in Xi’an brough together China’s President Xi Jinping with the leaders of the five Central Asian countries (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan). This summit and the subsequent March 2024 establishment of the joint secretariat and other mechanisms of free trade and communication brough the role of Xinjiang and the Central Asian nations into a new light. Several new transport infrastructure projects are under way, the most important of which is the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Highway and the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan highway and phase two of the China-Tajikistan Highway. Trade between China and the Central Asian nations reached US$ 90 billion in 2023, an increase of 27% year on year, and is poised to increase even more. Xinjiang takes the lion’s share of this trade.

China and Kazakhstan have many plans to enhance the China-EU Express Rail (CEER) capacity and add new routes to it, such as the Middle Corridor (also known as the Trans-Caspian International Transport Corridor) that would link China to the Black Sea from Kazakhstan’s Caspian Sea port of Aktau to Azerbaijan, Georgia, and also with a branch to Turkey.

The Central Asian nations, especially Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, are becoming more than a land-bridge between China and Europe. Their economies are booming with foreign direct investments from both East and West pouring into their emerging economies. With the New Silk Road, the disadvantage of being landlocked nations is disappearing. Their natural resources are coming into play in the international economy. The growth of their economies will be boosted by machinery and technology provided by the new industrial zones of Xinjiang. The case of Afghanistan and Pakistan, although less shiny examples than the Central Asian nations, are on a much better path towards development than the past 40 years of geopolitical proxy wars.

Further to the West, Iran and the Arab countries in the Gulf and Egypt are emerging as new economic centres. If you draw a circle that encompasses Iran, Arab Gulf states, Yemen, Ethiopia, Sudan, Egypt, Syria, Turkey and Iraq, what you get is one of the most interesting regions in the world in terms of economic potential. However, this region has been a geopolitical playground of global politics, with the Arab-Israeli conflict at its core. While the war in Gaza has brough the whole region to the brink of a regional war, it is still unable to diminish this region’s importance of the global economy. It is home to about two-thirds of the world’s known reserves of oil and gas. It has a unique geographical location between world continents and seas. It has a very large, very young, and relatively well-educated population of more than 500 million people and rapidly growing, surpassing the stagnating total population of the EU (448 million). Add to all this the fact that the sovereign wealth funds of the region contain more than US$ trillion generated largely by export of oil and gas. This wealth was previously mostly invested in Western financial and economic institutions and assets, in addition to real-estate projects. Currently, a certain portion of this money is repatriated to be invested in infrastructure and industrial projects at home and in productive economic investments in Asia and even Africa. The Asian Infrastructure Development Bank and the BRICS New Development Bank are in dire need for such fresh inputs. The severe oil shocks of 2014-2016, and 2020-202, when the oil price dipped to below 30 $ / barrel and caused real economic and financial crises for the oil exporting countries, represented very harsh lessons. Diversifying the economic activity and sources of income have become the battle cry of the governments of the region, with Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 as a good example of the shift taking place.

This area has slowly but certainly become a focus of China’s economic and foreign policy since President Xi presented his “1+2+3” policy in the China-Arab Summit of 2014. The December 2022 summit between President Xi and the leaders of the Arab World in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, highlighted the enormous potential that exists for cooperation, industrialization, and trade. “China is now the largest trading partner of the Arab states, with last year’s trade volume almost doubling from the 2012 level to 431.4 billion U.S. dollars,” said President Xi Jinping in his speech to the Arab leaders.

In his speech to the GCC leaders in Riyadh on December 10, 2022, President Xi outlined the concrete economic and financial measures China was offering to work with the GCC immediately. The “five points” Xi presented should be of interest to study for any serious analyst. They include long-term trade in oil and gas in local currencies, infrastructure projects extending to nuclear power, space exploration and space technology, telecommunications and AI, industrial projects, and transport infrastructure projects. One day before the China-GCC Summit President Xi and Saudi King Salman ben Abdul-Aziz reached a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership agreement. This partnership is symbiotic with Saudi Vision 2030. Immediately, 30 memoranda of understanding (MoUs) were signed between Chinese and Saudi entities. These were concretized as contracts worth US$ 10 billion during the China-Arab Business Forum in Saudi Arabia in June 2023.

The Irony is that when U.S. President Joe Biden visited Saudi Arabia in July 2022, he made it clear that “the bottom line is: This trip is about once again positioning America in this region for the future. We are not going to leave a vacuum in the Middle East for Russia or China to fill. And we’re getting results.” It seems that the complete opposite happened a few months later. Not only China was filling a huge vacuum left by U.S. lack of interest in building stronger economic partnerships, but the Gulf countries and OPEC continued coordinating oil export policies with Russia within the framework of OPEC Plus. The vacuum seems to come not from actions of Russia or China, but instead from the fact that the U.S. is solely focused on security and military matters in the region with no interest in trade and economic cooperation with the nations there.

In February 2023. Iran (a non-Arab country) finalised a 2021 25-year comprehensive strategic cooperation agreement with China, during the state visit by President Ibrahim Raisi to Beijing. Surprisingly. A month later, in March 2023, China brokered the Iran-Saudi Arabia restoration of diplomatic relations. By the end of the year 2023, Iran, Saudi Arabian, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, and Ethiopia were all admitted into the BRICS (Brazil, India, Russia, China, and South Africa) creating the BRIX Plus. These nations are also either full members or observers in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) which is increasingly moving from being a mere security cooperation organisation into an economic cooperation mechanism. Xinjiang plays a major role in all these architectures.

Securing the energy flows

China’s energy security in the coming decades will depend on securing, through cooperation and diplomacy, this whole region to the shores of the Red Sea. Central Asia and the Persian Gulf countries are the main suppliers of China’s oil and gas needs. Russia has also emerged as the complementary major energy exporter to China. China’s economic stability depends largely on the safe and continuous flow of oil and gas from these regions to its ports. Geopolitical tension can make strategic chokepoints like the Hormuz Strait and the Malacca Strait a major source of insecurity for China and its partners. Therefore, land-based energy corridors along the Economic Belt of the New Silk Road and Xinjiang will assume increasing importance and attention in the coming decades. Currently, four major pipelines carry around 55 billion cubic meters of natural gas annually from Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan to China through Xinjiang. This is exactly as much gas as the ill-fated Baltic-Sea based Nord Stream 1 was carrying from Russia to Germany before it was sabotaged in September 2022.

Conclusion

The withdrawal of the U.S. and NATO troops from Afghanistan in August 2021 was a major watershed, probably marking the end of the Great Game that lasted for almost three centuries. Using Afghanistan and other Khanates and stans as a security buffer zone and a destabilization source for both Russia and China have ended. With China managing successfully to end the threat of terrorism and separatism in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, and consolidating its relations with the Central Asian nations, and now through diplomatic relations with the Taliban-steered Kabul, it is moving towards securing the realm around it. Russia’s role remains strong in the region, and its intervention in January 2022 in Kazakhstan to prevent a colour revolution was decisive. Although a certain level of tensions between these countries and Russia still exists and attempts by the EU and the U.S. to persuade them to reduce their reliance on Russia and China continue, realities of geography and history cannot be changed.

With the Arab countries, Iran, and the central Asian countries emerging as key economic partners of China, geoeconomics is emerging as the key element of foreign policy rather than geopolitics. Economy will have a final saying in many of the issues that have determined the policies of the nations of the “heartland” of the Eurasian continent.